by Nun Nectaria (McLees)

Hieromonk Deiniol, the sole native Welsh Orthodox priest, the founder of the Wales Orthodox Mission, and pastor of the Church of All Saints in the North Wales mining town of Blaenau Ffestiniog, traveled with Road to Emmaus magazine in 2009 to ancient and little-known pre-schism shrines of the Welsh countryside. Along the way we talked of early Welsh Christianity, the effects of post-Reformation Calvinism, and the state of the Welsh Church today.

Hieromonk Deiniol, the sole native Welsh Orthodox priest, the founder of the Wales Orthodox Mission, and pastor of the Church of All Saints in the North Wales mining town of Blaenau Ffestiniog, traveled with Road to Emmaus magazine in 2009 to ancient and little-known pre-schism shrines of the Welsh countryside. Along the way we talked of early Welsh Christianity, the effects of post-Reformation Calvinism, and the state of the Welsh Church today.RTE: father, how did a native Welshman end up as an Orthodox priest in Blaenau Ffestiniog?

Fr. Deiniol: I originate from Anglesey, an island off the coast of North Wales, and I became Orthodox at the age of twenty, when I was living and studying in London. I became a monk in 1977, and was ordained a priest in 1979 by Metropolitan Anthony of Sourouzh, who gave me the task of opening an Orthodox church in North Wales. At that time, the nearest church was in Liverpool, which was very far for people from north-west Wales. After ordination I moved a few miles from where I was living to Blaenau Ffestiniog, where I’ve been for twenty-six years.

RTE: And what can you tell us about this remote and beautiful town?

Fr. Deiniol: The town of Blaenau Ffestiniog is a depressed post-industrial town in the middle of the mountains. It was a very busy town while the slate industry flourished, one of three or four such areas in north Wales, and in the 19th century, it employed many thousands of people. Unlike the other slate-mining areas in north Wales, extraction of the slate in Blaenau Ffestiniog took place underground. In other locations it was above ground, or at least in open pits, but here the slate was mined beneath the earth, and the conditions were terrible. Mines were often full of dust from blasting the slate, and smoke from the explosives.

The men worked in the dark with candles on their helmets. They were answerable to the mine’s steward and if they arrived at work a minute late they were sent home. They worked chained. A chain was fastened around their upper leg, and they were suspended from this chain, which was attached to a rod hammered into the slate face. In other countries, these working conditions are considered penal conditions, for example, in the old salt mines in Siberia. In the winter, the slate miners wouldn’t see the light of day. They started work before dawn and finished after dark.

Nevertheless, there was a sort of vibrant cultural life in those mining towns, partly due to the fact that these miners didn’t want bright young men to have to work in the same conditions. They would save money, for example, and gather pennies and subscriptions to send bright youngsters to the university. Many young men from that time owe a lot to their mining families and friends, who made sure that they didn’t have to go into the mines. In fact, those miners paid to set up the University of Wales.

In just such a way they built their nonconformist chapels, of which at one time there were forty-two in our town which, at its height, had a population of 12,000. Having all of these sectarian chapels was characteristic of Welsh society at the time.

That was the formative period for Blaenau Ffestiniog, but we have to realize that because the town is located very high up in the mountains at the end of a valley, in the normal course of events, no one would have thought of building a town there. It came into being only because of the slate mining industry, and is built in the shape of an inverted horseshoe—so you can be on one side of the town and look across the valley to the other side.

In addition to valuing culture, many people, of course, also valued their religious heritage, but as in most other places in North Wales, this was a very Calvinistic form of Protestantism. In the South Wales valleys, where coal mining was the dominant industry, Calvinism didn’t dominate in the same way. This is something we should return to when we analyze the logistics of what Orthodox mission involves in a post-Calvinist society.

RTE: When did the slate mining stop?

St. Tanwg’s Church, Llandanwg

Fr. Deiniol: It hasn’t stopped; it continues, but on a much-reduced scale. People sometimes compare the North Wales slate-mining areas with the South Wales coal-mining valleys. If you go to a place called Tylotrstown in the Small Rhondda Valley, you wonder where does Tylotrstown end and where does the next town, Ferndale, begin?

These villages run into each other in a row, whereas in North Wales slate-mining towns were quite separate communities, particularly Blaenau Ffestiniog, and there is a certain air of isolation here. Also, of course, after the decline of the industry, it became a post-industrial town, which means that this town, which produced an income of millions of pounds from which the local people never benefited, then became a place of unemployment.

We have all the characteristics of the postindustrial communities of north-east England that are one hundred times our size, and the Pennsylvania coal-mining areas in the States: high degrees of social exclusion, substance abuse, family breakup, the break-down of social cohesion.

So this is the town I live in, a very poor town, high levels of unemployment and many people with a sense of hopelessness. Nevertheless, they wouldn’t think of turning to church, because the Calvinist legacy is a very negative one. I’m not saying that everything was bad about the chapels; the Nonconformist tradition produced a genuine Christian spirituality with a real love of Scripture, a real love of God, and very fine hymnography, but it had a shadow side, and this shadow side was Calvinism and its censoriousness, being very judgmental and placing people in categories. It wasn’t known for its compassion for the frail and vulnerable, or for those whose lives took a negative turn.

RTE: Scotland also has many adherents of Calvinism, doesn’t it?

Fr. Deiniol: It does, and Calvinism was also strong in parts of South Africa, but the form of Calvinism there is not as extreme as the form that dominated in Wales, where the belief in ‘Double Predestination’ was adhered to.

RTE: What is ‘Double Predestination’?

Fr. Deiniol: The Calvinist doctrine is that God has predestined people from before the creation of the world for redemption. ‘Double Predestination’ is the belief that God has predetermined and preordained not only who shall go to heaven, but who shall go to hell. In other words, He has brought some human beings into existence, having already determined that they shall go to hell for eternity. They maintain that He has done this in His infinite Wisdom and that the logical contradiction between that and God’s infinite love is not for us to question and understand. So, the God of love becomes, in their theology, a tyrannical and arbitrary monster, whose excesses are far worse than the worst tyrants of human history, who only tormented people for a limited period of time. The God of Calvinism creates some people in order that they should suffer for eternity.

RTE: And this not only severs any notion of free will, but I imagine that you would have to take care to appear “good” to prove that you are one of the saved, or is that too simplistic?

Abandoned church, Llandudno, North Wales.

Fr. Deiniol: No, that’s very accurate.

“How do we know who is saved?”“Oh, by their fruits you shall know them.”

Accordingly, observable behavior becomes very important, and at a certain stage in the evolution of things, when conviction and faith are no longer so strongly present, this preoccupation with appearances becomes a very distinctive characteristic of these societies. That is certainly what I think happened in Wales. Also it means that people don’t look at the darker side of themselves, and don’t encounter their shadow. Darkness is then projected onto other people, so you have groups that are the scapegoats, the lowest of the low.

Communities are very hierarchical and there are people right at the bottom of the pile. In Wales, this emphasis on behavior also got linked up with the Temperance Movement, which, much as it may have been needed, divided the society into two—those who went to the chapel and those who went to the pub, those who drank and those who didn’t (or at least said they didn’t drink.)

To this very day, many Welsh people who go to the pub will not visit a church or chapel. The two locations are thought to be mutually exclusive locations, and those who frequent one of these places will usually hold the other place and its frequenters in contempt and think they will not be welcomed there! By now almost everybody does visit the pub, but the dichotomy persists and it is almost impossible to persuade people to visit a church. Furthermore, because every family was a ‘member’ of a Non-conformist chapel or of the Anglican parish Church, it means that people are still aware of their family ‘Church allegiance’.

They may still pay an annual fee for their family seat in a particular chapel, but never attend that chapel or any other place of worship, other than for baptisms, weddings, and funerals. However, they will use their ancestral allegiance to a particular denomination as a reason not to attend any other Church. An invitation to attend the Orthodox Church will therefore usually be met with a negative response. Typically, they might say ‘‘my ‘ticket’ (i.e. membership card which they maintain by payment of the rent for their seat in the chapel!) is in such and such a chapel.” Yet they may not have been there for 25 years.

Of course, as you’ve mentioned, Calvinism undermines any doctrine of free will. In fact they don’t believe in free will. Free will and predestination are opposing doctrines. This is perhaps what happens when you eliminate the role of the Mother of God from your theology, because it was of her own free will that she said,

“Be it unto me according to Thy will.”

At that point she was free to say, “No.” The redemption of the human race was in the balance at that moment. She could have said,

“This is too much, I can’t take this on,”

but instead she said,

“Be it unto me…”

So when you remove the Mother of God, and the very pivotal nature of her response, then the door is open to do away with the idea of free will in Christian theology, and the way is open for Calvinism. The Mother of God is our protection against Calvinistic doctrine. The Calvinistic doctrine that some are chosen for heaven, and others for hell, not only makes God seem very arbitrary, but it undermines any idea that God is the God of love and that our response to Him is a free and voluntary response.

RTE: In that case, you couldn’t possibly love Him yourself.

Fr. Deiniol: Yes—love is voluntary, not compulsory. We can only love God if we have free will. We might be frightened of Him, perhaps, or feel duty towards Him, but without free will we cannot love Him. Without free will our relationship with Him is not reciprocal. This attitude has created antipathy, and although people now don’t go to church, they know something—not theology, but the feel of Calvinism that permeates their culture. They keep their distance because they think they know what Christianity is, but it’s often a negative impression. For this reason, it would be easier to undertake a mission in Tibet than in a Calvinistic culture.

I imagine it will take a generation or two for people not only to consciously reject specific Calvinistic perspectives and teachings, but to rid themselves of its influence on their mentality. It has left behind a certain fatalism. These chapels have died very quickly. They are closing at the rate of one a week in Wales, which is a small country, and it’s as if people are glad to shake off the whole thing.

RTE: Do you think that after these generations pass, people will be ready to reconsider Christianity?

Fr. Deiniol: Because people free themselves doesn’t actually mean they will come to church, but that particular obstacle won’t be there. There will be other obstacles then. When people begin asking questions about the meaning of life, about the significance of things, they begin to touch on religious questions, but in general, people are not asking these questions, and I say this as one who has taught religious education for fifteen years here in Wales, and who has lived in this society most of his life.

RTE: Perhaps it’s a recovery period.

Fr. Deiniol: If it acts as a recovery period that would be very good. Of course, this is an attempt to provide some sort of diagnosis or analysis, and I’m not saying that I have answers as to what the strategy of the Orthodox Church in Wales should be. God does things in His way and His time, and it would be foolish of me to say,

“This is what we must do.”

But I think we won’t go far wrong if, for example, as Orthodox people in Wales, we try to demonstrate some care for people in their situations in life. for example, in our town there are high rates of unemployment. If our church can be instrumental in improving people’s lives so that they aren’t plagued by constant problems, this may be a way to show that God loves them and cares about them, and cares about their situations.

But I think we won’t go far wrong if, for example, as Orthodox people in Wales, we try to demonstrate some care for people in their situations in life. for example, in our town there are high rates of unemployment. If our church can be instrumental in improving people’s lives so that they aren’t plagued by constant problems, this may be a way to show that God loves them and cares about them, and cares about their situations.RTE: Do you have ideas as to how your parish can participate in that?

Fr. Deiniol: To be honest, although we are not numerous, many of us have been very actively involved in work in the community and for the regeneration of Blaenau Ffestiniog from the inception of our church. Orthodoxy believes not only in life after death, but in life before death. The quality of people’s lives is important. We are incarnate beings, not just souls, and we can’t be happy if we see people hungry or in anguish. We have to be concerned about people’s situations as a whole, in their totality.

RTE: Yes, and this approach has other 20th-century precedents. After World War II and the Greek civil war, there was massive unemployment and many Greeks were depressed and disillusioned with the Church. Fr. Amphilochius Makris, the well-known spiritual father of Patmos, said that the words of preachers and politicians were like throwing turpentine on the fire, and that only love and works of charity would bring them back to Christ.

Fr. Deiniol: Well, the Gospel actually says that, doesn’t it? Why should I consider preaching at people to be the main strategy? Why should they listen to me? For two centuries, they’ve listened to other preachers who didn’t make them feel good. I have no mandate from them. They didn’t ask me to come here and preach to them. On what basis would I assume that these people want to hear what I’ve got to say? That’s the first thing.

The second thing is that people do not go to church in Wales. I remember asking a young person,

“What would it take to get you to go to church?” He said, “A great deal of courage to actually be seen coming into the building by my friends.”

This is very different from many countries, even from the States, as I know from my visits there. But we have to be aware of what things are like in the United Kingdom and what things are like in Wales. And as I’ve tried to explain in giving this Calvinistic background, I’m not surprised that people don’t want to come to church.

This not to say we don’t get any people coming into church. In fact, we get many visitors and my parishioners are a mixture of nationalities. For Christmas we were ten nationalities, and there are also foreign Orthodox students at the universities and colleges where I am chaplain. We conduct our services in a number of languages, according to the need on any particular Sunday. We’ve been very fortunate in the support we receive from our hierarch, Bishop Andriy of Western Europe, who is a member of the Synod of Bishops of the Ukrainian Church of the Diaspora, within the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

We are officially called The Wales Orthodox Mission, of which I am the administrator. In fact, the term “mission” is not used very much in the U.K. by the Orthodox Church, but I think it is very important to state what we are. We are not a chaplaincy looking after a separate ethnic minority, nor are we a well-established church full of people who have become Orthodox (although there are increasing numbers). We are a mission. And I think that any church in Wales, whether Orthodox, Catholic, Anglican or anything else, should at this point call themselves a mission, because that is the nature of the situation.

The Wales Orthodox Mission is the contact point between the Orthodox Church and Welsh institutions. If Welsh organizations wish to be in touch with the Orthodox Church, they contact us, and we get many groups visiting us from churches and societies. I’m often asked to give talks and if subjects such as Eastern Europe or certain theological or social issues are being discussed on the radio or TV, they sometimes ask me for an interview on these topics as well. So our church is present and active, but I hope in a way that corresponds to the needs, realities, and possibilities that exist at this stage in Welsh cultural history.

RTE: We were told that you were invited to lead a prayer at the opening of your national parliament, the Welsh Assembly.

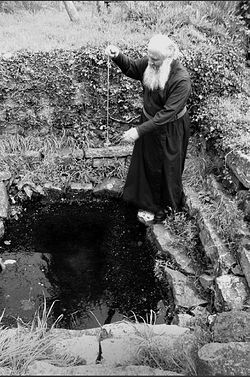

Fr. Deiniol blessing St. Engan's well, Llanengan

Fr. Deiniol: This is quite an interesting history. Wales lost its independence in government 700 years ago, and approximately six years ago, we received our own government again, not completely independent, but with certain powers. There was an ecumenical service to celebrate the opening of the Welsh Assembly Government, which took place at the Anglican cathedral in Llandaff, Cardiff. The Orthodox Church, amongst other churches, was invited to make a contribution to the format of the service. I prepared two prayers. Each prayer had a response, and as the response I included,

“All you saints of Wales, pray to God for us.”

The ecumenical organizers came back and said that they didn’t think this was acceptable. (Invocation of the saints, of course, had been outlawed during the Protestant period.) My response was,

“If you invite an Orthodox priest, you get an Orthodox response and an Orthodox contribution. If this is not acceptable, why do you ask us in the first place?”

At that point I felt that the ghost of Thomas Cromwell was striding rampantly through Wales. Thomas Cromwell was Henry VIII’s henchman and operator who closed all the monasteries throughout Britain, wrecked the shrines and relics, and destroyed the altars. I thought, “Well, they are still unwilling to invoke the saints,” and was about to write a fax that evening to say words to this effect, but at the moment I was about to send this letter, another fax arrived saying that the prayer was alright. So this prayer was used and the response was used.

Now the interesting part is this. on that occasion, the Queen of England, her husband the Duke of Edinburgh, and her son, Charles, Prince of Wales, were all present at the service. Normally, for security reasons, the three do not travel or appear together. So when that prayer was said, and the whole congregation responded,

“O, all you saints of Wales, pray to God for us!”,

this was the first time such a phrase had been used in that cathedral since the Reformation—with the successor of Henry VIII, the king who had originally made such an invocation illegal, present and taking part in the service. That was not an insignificant event, I think.

RTE: Wonderful. Can we go back some centuries and talk about how Wales, as we know it now, came into being?

Fr. Deiniol: The process was complicated. We first had the Celtic-speaking native British, who were pushed west as the invading Angles, Saxons, and Jutes gained ascendancy. In some places the original population of Britons probably mixed with them, in other places not. In Strathclyde, now in Scotland, for example, the Welsh language was spoken until the twelfth century, and the first Welsh poetry is found in Catterick in northern Yorkshire in England. Even to this day, when we speak in Welsh of the “old North,” we mean the area around Strathclyde.

At a certain point, various of these invading tribes developed kingdoms, such as in Mercia, where a wall was built separating the Brythonic-speaking Britons who had gone west, from the conquering tribes. In about the 7th century, the word “Welsh” began to be used by the English Anglo-Saxons, meaning “foreigners,” and the Welsh called themselves Cymry, which means “the brethren” or “compatriots.” We cannot speak of a separate England, Wales, and Scotland until that point.

So, the original Brythonic-speaking people in the old North, in Devon, Cornwall, and Wales, were now physically separated from one another. The Welsh language was eventually lost from the “old North,” and so it is no longer possible to identify the descendants of the ancient Britons who lived there. The Scots are not their descendants, but descendants of Irish migrants who settled there. That is why Scottish and Irish Gaelic are almost the same language. The Cornish language died in the 18th century. The only descendants of the ancient Britons who can still be identified are the people of Wales, and this is because we have preserved our ancient language. What we now call “the Welsh” is the identifiable remnant of the original people of the British Isles.

RTE: We tend to think of centers of early Romano-British Christianity as being near such places as York. When the Romans pulled out in the fifth century, did Wales also have a fully-established hierarchical church?

Fr. Deiniol: of course. They say that Bangor-in-Arfon in North West Wales was a diocese in the sense that we use the word now, as a territorial area from the sixth century. Bede talks about a monastery in Bangor-on-Dee (another Bangor) with 2,000 monks. Certainly, there were Celtic bishops as well.

Of course, we can’t speak about “The Celtic Church,” as if it was an organized entity that incorporated what we now call Brittany, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland into an identifiable independent body. It was part of the worldwide Church. It was catholic—but not in the contemporary sense of “Roman Catholic”—in faith and doctrine. There was coming and going, and there was much interest on the Continent about what was happening in Britain. Many writers speak of early Christianity here, and early fathers of the Church mention it as well—origen, Lactantius, Tertullian, Eusebius.

They knew of the Christian Church in Britain, and monks used to travel to the East from the Celtic-speaking lands on pilgrimage. There was evangelization along the trade routes, and our monks certainly went to see monastic life in Egypt, the Holy Land, Rome, and Constantinople. Monasticism here seemed to resemble more the Lavra system than the classical coenobitic monasteries that evolved in the West. There is also a tradition that the Celtic bishops St. David, St. Teilo, and St. Padarn were all consecrated by the patriarch of Jerusalem. According to tradition, one was given a sakkos, the bishop’s vestment, another, a portable altar, and the third, a bishop’s staff.

So there were connections with the East, but we don’t have to show a connection with the East to prove that this church of the Celts was Catholic and Orthodox in faith and doctrine. Yes, they had their local customs, such as shaving their head in a certain way for the monastic tonsure, as we find local customs today in various local Orthodox churches. And, as within Orthodoxy today, they had different calendars. After the Synod of Whitby, when the Church of the Celtic peoples adapted its local customs to conform to those of Rome, it came under Canterbury and thereby under Rome. So when the Great Schism came about, it was part of the patriarchate of the West, and went with the western Churches. Canterbury remained the primatial see of Britain.

RTE: How did the 11th-century Norman invasion affect Christian Wales?

Fr. Deiniol: In Wales, the Normans established many monasteries. In fact, all the big abbeys were established by them. The most significant thing about this was that, while previously the monasteries had followed the Orthodox tradition of being independent and generally self-ruling, now each monastery had to belong to one of the Western religious orders. The Welsh often chose the Augustinians, as being perhaps the nearest to the way of life they were accustomed to. There were also many Cistercian foundations in Wales, such as the monastery in Strata Florida. This is where the history of Wales, called “The Chronicles of the Princes,” in Welsh, Brut-y-Tywysogion, was written. The history of Wales begins with the death of St. Cadwaladr, the last Briton—i.e. Celt, to be king of Britain before the Saxons obtained the crown. He is the patron saint of The Wales Orthodox Mission. He was known for his compassion, otherworldliness, and generosity—giving away his possessions to those who had lost theirs and caring for the multitudes who were afflicted by a terrible plague which visited the land in those days.

RTE: With such a rich heritage, what allowed the Welsh and Scots to make such a radical change from traditional Catholicism and a Reformation-imposed Anglicanism, to Calvinism?

Fr. Deiniol: By the 18th century, the Anglican Church in Wales was pretty moribund. It was led by English, non-Welsh-speaking absentee Anglican bishops. Many of the clergy were also absentee and did not speak the language of the people (by no means everyone in Wales could speak English in those days).

Fr. Deiniol: By the 18th century, the Anglican Church in Wales was pretty moribund. It was led by English, non-Welsh-speaking absentee Anglican bishops. Many of the clergy were also absentee and did not speak the language of the people (by no means everyone in Wales could speak English in those days).When the Methodist Revival broke out in the U.K. and spread to Wales, John Wesley and Whitfield, his colleague, came to an agreement that Wesley would have England as missionary territory and Whitfield would take Wales. Methodism spread in Wales through the efforts of great “revivalists” like Howell Harris, Daniel Rowlands, and especially the magnificent hymnographer, William Williams of Pantycelyn, whose hymns are, by any measure, classics comparable to the great hymnographers of any Christian tradition, East or West. Thus, the people of Wales were offered a vibrant and rich religious life, in their own language.

Methodism became a popular movement—unlike the highly Anglicized Anglican Church in Wales which was essentially the Church of the landowners and to which the ordinary Welsh people may never have been very attached since the Reformation. The ordinary, poor Welsh people now had a form of Christianity of their own which flourished and produced some good fruit.

However, Whitfield was a Calvinist and so the form of Methodism that spread in Wales was Calvinistic Methodisim. When a Welsh person speaks of Methodism, he or she generally means this Calvinistic variety also known as the Presbyterian Church of Wales (the title they prefer these days). Methodism in England followed Wesley’s theology which was based on the teaching of Jacobus Arminius,which emphasizes free will as opposed to Calvin’s predestination.

Later on, Wesleyan Methodism also came to Wales, but it was a minority denomination here and strong only in certain specific areas. However, the Calvinists maintain (and I have heard this point being made by a Calvinist minister in my house a few years ago) that the ‘Wesleyans’ have no right to be in Wales owing to the agreement between Whitfield and Wesley.

I must say that the ethos of each of the two forms of Methodism was very different. They had very different cultures from each other. There was even a ditty about the Calvinists: ‘Nasty, cruel Methodists (i.e. Calvinists) who go to chapel without any grace….’

RTE: Have the Catholic and Anglican Churches returned in any force since?

Fr. Deiniol: The Roman Catholic Church, which was illegal for hundreds of years, only returned in the 19th century, although a few “recusant” families who could afford to pay the fines, remained Catholic. Accordingly, most Roman Catholics in Wales are not Welsh, but are usually partly of Polish or Irish extraction. There are some Welsh Roman Catholics but they aren’t numerous.

After the rise of Protestant Calvinism, the Anglican Church became a minority church compared to the Non-conformist denominations such as Baptists, Congregationalists, and Calvinists. only a small proportion of Welsh-speaking or culturally Welsh people belonged to it. This may still be true to some degree. It was only in the 20th century that the Anglican Church in Wales gained its independence from Canterbury and became disestablished.

So, we can say that this is a good time for Orthodoxy as a continuation of the Undivided Church, to be in Wales. None of the other churches dominate Welsh religious and cultural life, and people are not so sectarian in their mentality—it doesn’t mean as much to them now that they are Baptists or Calvinists. There is a very friendly atmosphere. Also, the prejudices against saints and their veneration (customs such as praying at shrines and holy wells, which reflect the sacramental understanding of life) are now more acceptable. At least we aren’t in the position of confrontation, and that is helpful.

RTE: Are people becoming more interested as they see your attempts to recover their heritage?

Fr. Deiniol: No, I don’t think so. The awareness of the saints is too lost. They are mostly remembered in place-names—for example, a majority of places in Wales begin with the prefix “Llan.” This can mean the church building, but it also means a Christian settlement, usually founded by a Christian saint. In many cases we are talking about the period of the Anglo-Saxon invasion, when the original Celtic-speaking British peoples began moving west. A saint might land on a coastal area, as did St. David, the patron saint of Wales, who went to a place called Vallis Rosina, “Valley of the Roses,” to live as a monk. The pagan tribes are at first hostile to him but eventually people are attracted by the holiness of his life and become Christian; a community forms, and around the community, a village. This is almost identical to what St. Sergei of Radonezh did in Russia, founding new hermitages and monasteries as he moved deeper into the forest.

These new communities that came into being because people were attracted by the saint who lived there, are called Llan, and very often in Welsh place-names, the name that follows Llan is the name of a saint: Llandanwg—the Christian settlement and Church of St. Tanwg, or Llandudno—the Church of St. Tudno.

What is this country that we now call Wales? It is the sum total of the Llans, these places created by saints, communities that didn’t exist before they came. As we travel these roads we go through one Llan after another, and each one is a saint’s name. This is why I use the expression, “Wales is a nation created by saints.”

But, even with such a rich history, we need more to awaken us than an understanding of place names. The young people in Russia, for example, still have a link with their spiritual past after the collapse of Soviet atheism—their grandmothers were still Orthodox Christians—but what we’ve had here was a much longer break. of course, after the Great Schism, I’m sure that very little changed, and much in Roman Catholic practice would have been indistinguishable from Orthodoxy for a very long time afterwards.

Even that break, however, goes back a thousand years, and the Reformation, which was largely destructive of tradition, goes back 400 years.

When we acquired our church, the Metropolitan suggested that we dedicate it to “All the Saints of Wales.” The idea is that when the church is finished with icons and frescoes, a person from any part of Wales will be able to come here and find his saint. This is part of our task, recreating this link with history, and this is done by things like the service to mark the opening of the Welsh Assembly, and the opportunity to give talks and welcome visitors to the church. our mission exists on various levels and different fronts.

RTE: And the interest will not only be local. We come across many interesting accounts of the strong appeal that the Celtic culture has, especially for young people, in many parts of the world.

Fr. Deiniol: of course, wonderful things have survived, such as The Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels. The art and imagery are amazing. The Christian Celts had developed a profound and deeply Christian culture. It’s not surprising that this should be of interest to people in other countries.

Orthodox youth in former Soviet countries or the emigration often think of their ancestral churches as something rather ethnic or old-fashioned. other things appear more interesting to them. But it’s a little bit like the Trojan Horse isn’t it? If they become interested in Celtic history and culture, they will soon find that inside, at the very core, is their own Christian faith.

The question for us is how we can encourage our own young people to be remotely interested in anything Christian whatsoever. As an old colleague of mine, Archimandrite Barnabas—the first Welsh Orthodox priest—used to say, the cultural legacy of Calvinistic teaching seems to have provided an immunization against all religious search and questions.

RTE: May God give the blessing.

From: Road to Emmaus, Winter 2009, No. 36.

Click:

The Spirituality of the Celtic Church

Orthodoxy In An English Village

The “Orthodox Option” For Anglicans

OUR TALENT OF FREEDOM & SOME PITFALLS

Ancient Faith Radio Orthodoxy In An English Village

The “Orthodox Option” For Anglicans

OUR TALENT OF FREEDOM & SOME PITFALLS

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου