by Fr. Sergius Model Russian Orthodox priest in Brussels

and the secretary of the diocese of the Patriarchate of Moscow in Belgium

and the secretary of the diocese of the Patriarchate of Moscow in Belgium

From here & here

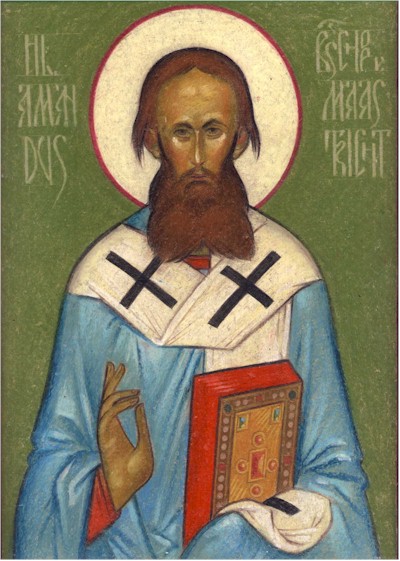

Saint Amandus of Elnon - Feb 6 Reposed in the Lord † 675. Born near Nantes in France, he lived as a hermit in Bourges for fifteen years. At the age of thirty-three he became a bishop and preached in Flanders in Belgium, Carinthia in Austria and among the Basques in Spain. He founded many monasteries in all these places, of which the best known is Elnon near Tournai, where he went in his old age and reposed, aged over ninety.

Modern History

Among the changes which took place over the years, was the arrival of new personalities such as that of His Grace Paul (Golychev) (1914-1979): first he was a priest in Belgium, then became a bishop in the USSR, then came back to Brussels in 1976; and above all of Archbishop Basil (Krivocheine) (1900-1985), a monk of Mount Athos and a theologian scholar who had succeeded Archbishop Alexander (metropolitan since 1959) in 1960. A specialist of the Church Fathers, Archbishop Basil did not hesitate to intervene in the questions concerning what was actually happening on the ground in the Russian Church in the Soviet Union.

The Greek parishes of this diocese keep their linguistic and cultural identities for the Hellenistic community; the diocese also has some ‘western’ parishes celebrating in the local languages: in Courtrai, Bruges, Brussels and in Ghent, where a church in the Orthodox style with a cupola was recently built (2001). Bishop Athenagoras Peckstadt (the son of Father Ignatius) is responsible for these communities. An interesting experiment is being made in the Greek parish of Peronnes (Binche) to translate into French the tradition and chants of Byzantine origin. For some years a Georgian parish has functioned in Brussels, affiliated to this diocese.

Selective Bibliography - L’Eglise orthodoxe en Belgique, Annuaire, Ghent, ed. Apostel Andreas (annual). - Patriarcat œcuménique, Sainte Métropole de Belgique, Calendrier 1999 (in Greek), Brussels, 1999. - Bieliavsky, N., ‘Le Cardinal Mercier et l’émigration russe en Belgique’, Irénikon. Revue des Moines de Chevetogne, Chevetogne, t. LXXVI, 2003, pp. 179-198. - Coudenys, W., Leven voor de Tsaar. Russische ballingen, samenzweerders en collaborateurs in België, Leuven, Davidsfonds, 2004. - Metropolitan Evlogy, The way of my life (in Russian), Paris, Ymca-Press (1947); French translation, Paris, Presses de Saint-Serge, 2005. - Fontaine, G. (éd.), Mélanges pour un cinquantenaire (à l’occasion du 50e anniversaire de la paroisse orthodoxe russe de Liège), Liège, 2003. - Lahou, G., ‘Libres propos : la reconnaissance du culte orthodoxe en Belgique’, Bulletin de la Communauté orthodoxe de la Sainte Trinité, Brussels, June-July 1988 and November-December 1988. - Model, S., ‘Les Eglises orthodoxes locales : L’Eglise orthodoxe en Belgique’, ACER-Tribune, n°8, Paris, June 1986, pp. 55-64. - Model, S., Histoire de l’Archevêché orthodoxe russe de Bruxelles et de Belgique, éd. de la Paroisse orthodoxe de-la-Protection-de-la-Sainte-Vierge, Brussels, 1996. - Model, S., ‘L’Eglise orthodoxe en Belgique. Hier, aujourd’hui, demain’, Le Messager orthodoxe, n°138 (I), Paris, 2003, pp. 68-83. - Model, S., ‘Un évêque russe en Belgique : Monseigneur Basile Krivochéine (1900-1985)’, Revue de la Fondation pour la préservation du patrimoine russe en Belgique, n°2, Brussels, November 2005. - Nedossekine, P., The St-Nicholas Cathedral of the Russian Orthodox Church in Brussels (in Russian), Brussels, ed. of Saint Nicholas Church, 2e ed., 1999. - Peckstadt, A.Y., ‘Korte historische schets van een permanente orthodoxe aanwezigheid in België’, De Orthodoxe Kerk in België, Jaarboek 1987-1988, Ghent, ed. Apostel Andreas, 1987. - Peckstadt, A.Y., Découvrir et vivre l'Orthodoxie en Belgique. Le cheminement de l'Archiprêtre Ignace Peckstadt vers l'Eglise orthodoxe, Bruges, ed. Apostel Andreas, 2001. - Peckstadt, I., ‘Quelques aspects de l’Orthodoxie en Europe occidentale’, Actes du Colloque sur l’Orthodoxie dans le monde, 27-28 février 1984, Paris, éd. du Comité orthodoxe des amitiés françaises dans le monde, 1985, pp. 13-14. - Ronin, V., ‘The Russian religious life in Antwerp (1920-1960)’ (in Russian), Slavica Gandensia, n°26, Ghent, RUG, 1999, pp. 117-160. - Sollogoub, S. (ed.), The Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, 1918-1968 (in Russian), New York, ed. Russian Ecclesiastical Mission, 1968. - Tamigneaux, N., Le cardinal Mercier et l’aide belge aux Russes (academic dissertation in history, UCL), Louvain-la-Neuve, 1987. - Wener, J., L’émigration russe blanche en Belgique durant l’entre-deux guerres (academic dissertation in history, UCL), Louvain-la-Neuve, 1993.

Orthodox Saints of Belgium

Early origins

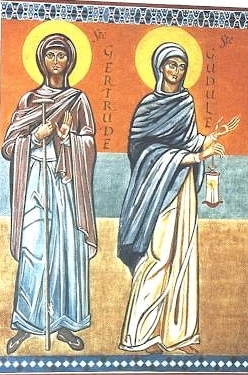

Situated in the Latin and Germanic borders, the regions of the future Belgium and of the future Luxemburg have been evangelized since the first century; several martyrs gave their lives there. After the germanic invasions, when stability was re-established, Christianisation was able to develop in a deeper way. The 7th century is called the ‘century of saints’, with Saint Amand, Saint Remacle the apostle of Ardenne, Saint Lambert of Liège and Saint Gertrude of Nivelles. The following centuries were marked by the activity, among others, of Saint Hubert and of Saint Godelieve. As these regions were under the Patriarchate of Rome, after the schism of the 11th century they were separated from the Orthodox Church. Contacts with Orthodoxy stopped, except for some events such as the visit of Peter the Great of Russia to what today is Belgium in 1717, or the marriage of Prince William of Orange to the sister of Tsar Alexander I in 1816.

|

| Saint Amandus of Maastricht |

As for the modern period, the first place of Orthodox worship in Belgium was organized in the second half of the 19th century when, in 1862, a chapel dedicated to Saint Nicholas was established by the Russian embassy in Brussels and served by priests sent from Russia. This was the only Orthodox church in the country until 1900, when a second church was created in the harbour city of Antwerp for Greek sailors and merchants. In 1926 another Greek church was opened in Brussels and remained for a long time the main Greek parish in Belgium.

The Orthodox presence in Brussels is marked above all by the emigrations of the 20th century, among them by the Russian one. The Revolution of 1917 provoked the exile of over a million Russians of whom about 8,000 came to Belgium. The Orthodox churches, perceived by the refugees as shelters, became at that time spiritual and material rallying places; new parishes were created everywhere.

In the 1920s and 1930s Russian churches were founded in several places: in Antwerp, Charleroi, Ghent, Liège, in the Russian orphanage of Namur and in the university town of Louvain (thanks to Cardinal Mercier). These churches were installed in private houses, in warehouses or in garages and served by clergy from the emigration of which here are some names: Fathers Peter Izvolsky, George Tarassov, the future archbishop in Paris (1893-1981), Vladimir Feodorov, Paul Golychev, future archbishop in Russia (1914-1979) and Valent Romensky.

During those years some jurisdictional problems also arose in the emigration, which were linked to the division of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR). In Brussels, in 1926-27, some parishioners of the Church of Saint Nicholas broke their contact with Metropolitan Evlogy (Exarch of the Russian parishes in Western Europe, Rue Daru, Paris) in order to follow the bishops of the ROCOR headed by Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky); then they created their own parish served, among other priests, by Fathers Basil Vinogradov and Alexander Chabachev, then by Father Tchedomir Ostojic. In Brussels, in 1935, the same jurisdiction erected a church, which looked Orthodox, with a cupola in the Russian style of the 16th century. Dedicated to the memory of Tsar Nicolas II, to his family and to other victims of Bolshevism, this beautiful looking church, consecrated to Saint Job, in 1950, was directed by Bishop John (Maximovitch) (1896-1966), who was titled ‘of Brussels’ from 1950 to 1962, but resided in France; then by Father Dimitri Khvostov.

Except for these latter parishes, all the other Russian parishes in Belgium were then depending on Metropolitan Evlogy, and, since 1929, on his auxiliary in Belgium, His Grace Alexander (Nemolovsky) (1880-1960). At the arrival of this first Orthodox bishop in Belgium, the parish of Saint Nicholas became a parish-cathedral, and Brussels then had an Episcopal Orthodox seat. The Belgian state confirmed this situation by a royal decree in 1937 which recognized the diocese giving it the status of an establishment of public use, and to its superior the title of Russian Orthodox archbishop of Brussels and of Belgium.

During World War II and the occupation of Belgium by the Germans, the Orthodox of Belgium had difficult times: some resisted the Germans authentically (such as Archbishop Alexander who was arrested in 1940 and deported to Germany), while others wished the victory to Hitler who, according to them, would liberate Russia from Bolshevism. Some parishes (such as the one in Antwerp) stopped functioning, whereas others (such as in Liège) hardly escaped total destruction. In Liège a new church with five little cupolas was built after the war and consecrated in 1953.

After World War II, the situation of the Orthodox Church in Belgium changed a lot; the Church of Saint Nicholas, under the direction of Archbishop Alexander, who had come back from captivity, went under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Moscow in 1946, while other Russian communities disappeared over time (Ghent, Leuven).

In the 1950s, an important Greek immigration came to Belgium, for economic reasons. Many of them were working in coalmines. The Greeks then constituted the most important Orthodox community (about 27,000 people) and the best organized one. About a dozen parishes were created around the country served by priests such as Father Emilianos Timiadis (future metropolitan and representative of the Patriarchate of Constantinople at the World Council of Churches in Geneva) and Father Panteleimon Kontoyiannis. In 1969, the Patriarchate of Constantinople created its own archbishopric, the metropolitanate of Belgium and exarchate of The Netherlands and Luxemburg, and appointed His Grace Emilianos (Zacharopoulos) as the first metropolitan. In 1974, His Grace Panteleimon (Kontoyiannis) became his auxiliary and, in 1983, succeeded him.

|

| Saints Gertrude and Gudula of Nivelles |

Among the changes which took place over the years, was the arrival of new personalities such as that of His Grace Paul (Golychev) (1914-1979): first he was a priest in Belgium, then became a bishop in the USSR, then came back to Brussels in 1976; and above all of Archbishop Basil (Krivocheine) (1900-1985), a monk of Mount Athos and a theologian scholar who had succeeded Archbishop Alexander (metropolitan since 1959) in 1960. A specialist of the Church Fathers, Archbishop Basil did not hesitate to intervene in the questions concerning what was actually happening on the ground in the Russian Church in the Soviet Union.

The growth of Orthodox in Belgium, the arrival of new personalities and the birth of an ecumenical atmosphere drew the attention of the local authorities. Some Catholic churches were lent or sold to the Orthodox, such as the one in the ‘Stalingrad avenue’ (near the Brussels South Station), which became the Greek cathedral of Belgium.

Step by step it became necessary however for the children of emigrants or for Westerners who became Orthodox to profess Orthodoxy in the local languages. This was well understood by bishops like Archbishop Basil (Krivocheine) of Brussels and Archbishop George (Tarassov) of Paris (Rue Daru): French speaking and Dutch speaking communities were created in the years 1960-1970, after a fruitless attempt in 1935-40. Then French speaking and Dutch speaking communities were opened: in Brussels, the parishes of the Protection of the Virgin (Father Joseph Lamine) and of the Holy Trinity and of Saints Cosmas and Damian (Fathers Peter Struve and Marc Nicaise); and in Ghent that of Saint Andrew (Father Ignatius Peckstadt).

From that time on, the Orthodox were better integrated in Belgian society, in particular after the Second Vatican Council (1962-65). Since then diverse activities (conferences, congresses, retreats and week-ends of reflection, youth movements, sessions of icon painting, etc.) have a certain impact. One can note a certain interest in the Orthodox Churches when Orthodox Patriarchs visit the country, for example when Patriarch Justinian of Romania came in 1972, and when Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople came in 1993, 1994, 1996 and 2004.

As for the Belgian authorities they mark their benevolence towards the Orthodox, for example when King Baudouin visited the Orthodox parish in Ghent in 1980, and especially when Orthodoxy was recognised as an official religion in Belgium in 1985 (and in 1998 in Luxemburg). Thanks to this recognition and to the action of diverse people, the Orthodox Church has become a real living reality in the ecclesial scenery of Belgium and Luxemburg today.

Present Situation

Today there are between 70,000 and 80,000 Orthodox Christians in Belgium. In Luxemburg, there are about one thousand faithful. About 4 bishops living in the country, 52 priests and 10 deacons of the diverse jurisdictions serve about 45 places of worship.

The Archbishopric (or Metropolitanate) of Belgium and Exarchate of The Netherlands and Luxemburg (Greek diocese of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, with its seat in Brussels) has 23 parishes in Belgium and 3 in Luxemburg (a Greek, a Romanian and a Bulgarian parish). The archbishopric is led by Metropolitan Panteleimon (Kontoyiannis), who is assisted by two auxiliary bishops, Maximos (Mastichis) and Athenagoras (Peckstadt). As exarch of the Patriarchate of Constantinople for the Benelux countries (Belgium, Luxemburg and The Netherlands), he is considered as the ‘first’ Orthodox bishop of the three countries and he also represents the Orthodox Church (including all jurisdictions) to the authorities of Belgium and Luxemburg.

|

| Saint Lambert of Liège |

The Greek parishes of this diocese keep their linguistic and cultural identities for the Hellenistic community; the diocese also has some ‘western’ parishes celebrating in the local languages: in Courtrai, Bruges, Brussels and in Ghent, where a church in the Orthodox style with a cupola was recently built (2001). Bishop Athenagoras Peckstadt (the son of Father Ignatius) is responsible for these communities. An interesting experiment is being made in the Greek parish of Peronnes (Binche) to translate into French the tradition and chants of Byzantine origin. For some years a Georgian parish has functioned in Brussels, affiliated to this diocese.

It is worthy of note that this diocese has a Centre of theological training founded in 1997 by Father Dominique Verbeke and linked with the Orthodox Theological Institute Saint Sergius in Paris. It organizes the programmes of Orthodox religious teaching for the public schools of Belgium. The diocese is also providing Orthodox presence for the Belgian medias and the Orthodox chaplaincy in the hospitals, jails and airports of the country.

The Belgian diocese of the Patriarchate of Moscow (archbishopric of Brussels and Belgium, with its seat in Brussels), has 11 communities including a monastery in Pervijze (near Dixmude, on the Belgian side) since 1976, and, since 2000, a little convent in Trazegnies (near Charleroi). Since 1987 the diocese is presided over by Archbishop Simon (Ishunin) who is also provisionally in charge of The Netherlands. These parishes include longstanding Russian emigrants or their descendants, new emigrants, as well as Belgians and other Westerners. The offices and liturgies are celebrated in Slavonic, French or Dutch, according to the communities.

In the frame of its representation by the European institutions, the Patriarchate of Moscow also opened in 2002, in Brussels, a church, which was under the direct administration of the Patriarch. The same year Queen Paola visited it. This church was integrated into the diocese in 2005.

The archbishopric for Russian Orthodox Churches in Western Europe (Patriarchate of Constantinople, Rue Daru), which until 2003 were presided over by Archbishop Sergius (Konovaloff) (1941-2003), includes 4 parishes, which are put together with the deanery in northern France; the dean is Father Guy Fontaine, of Liege. The offices are celebrated in Slavonic, French and Dutch, according to circumstances. When he was elected as archbishop in Paris (Rue Daru), Archbishop Sergius (Konovaloff), former priest in Brussels, used to come back regularly and visit these communities. His successor, Archbishop Gabriel (De Vylder), is also Belgian, but he resided for a long time in The Netherlands. Until his election he served the parish of Liege and was in charge of the vicariate of the archbishopric for the Benelux countries.

Three parishes, two in Brussels and one in Luxemburg (a Orthodox looking church with a cupola built by Father Sergius Poukh) are under the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. There are aged Russian people as well as new faithful from diverse origins. These parishes are under Bishop Michel (Donskoff) who resides in Geneva (Switzerland).

These Greek and Russian communities gather faithful who integrated into the western reality and who have learned to use different languages during the celebrations as well as to take into account the environment where they live. However, the great flux of new emigrants from Eastern Europe may change this situation.

Let us also note the existence of three Romanian communities (in Brussels, Antwerp and Liege), of a Bulgarian parish and of a Serbian parish (both in Brussels), which depend on their respective mother Churches, through the dioceses of Western Europe whose seats are situated outside Belgium.

There are also three parishes under the Ukrainian Church in Exile. In Genk in Limburg a beautiful church was built in Ukrainian baroque style. The Patriarchate of Constantinople has received these communities in 1990; they seem to keep isolated from the other Orthodox communities in Belgium.

As a whole, even though there is no Orthodox Episcopal organ of coordination in Belgium, the links between the Orthodox communities are brotherly. One of their common manifestations is the celebration of the Sunday of Orthodoxy which every year gathers the representatives of the all the jurisdictions in Brussels.

Other signs of pan-Orthodox collaboration can be seen through some organisations (such as the Orthodox Fellowship in Brussels or the local movement of Orthodox Youth linked to Syndesmos) where Orthodox of different jurisdictions collaborates. There are also other events organized in common, such as the Orthodox congresses organized by the Belgian Orthodox Fellowship (in Bruges-Maele in 1972, in Natoye in 1977 and in Blankenberge in 2000); as well as the congresses of the Orthodox Fellowship in Western Europe (in Ghent in 1983 and in Blankenberge in 1993 and in 2005). Some parishes publish a bulletin. Some books and reviews are also published in common by Orthodox of Belgium.

There are ecumenical relationships: some Orthodox takes part in different ecumenical associations (ACAT, ‘Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture’, ‘Pax Christi’) and in official institutions. One may consider that the Orthodox presence in ecumenical circles in Belgium could be stronger, even if the Orthodox are a minority in the country.

One cannot keep silent about the fact that some Orthodox Churches have their own representations in the European institutions in Brussels. The Patriarchate of Constantinople set the first representation in 1995, followed by the Churches of Greece, Russia and Romania. Other Churches may follow their example.

This panorama of Orthodoxy in Belgium and in Luxemburg would not be complete without speaking of the legal situation. In 1985, the Orthodox Church was recognized by the Belgian state as an official denomination, as is the case for the Catholic, Protestant, and Anglican denominations, and Jewish and Muslim religions. This legal recognition, completed by decrees in 1988, does give rights to the Orthodox of Belgium and at the same time imposes duties. An identical recognition was given in the Great Duchy of Luxemburg in 1998. The rights are linked to the recognition of determined parishes with salary for the priests as well as to the possibility of involvement in the medias (with Orthodox programmes on radio and television), in the hospitals and jails; besides other confessions and religions (Catholic, Protestant, Anglican, Jewish and Muslim) the Orthodox may organize courses of Orthodox religion in public schools (since 1988-1989 in Flanders, and since 1997 in the French speaking part of the country). The imposed duties imply not only a respect for the conditions of application of these dispositions, but also to understand that the acts of the Orthodox community have, from now on, feedback in Belgian society.

As is the case for all the Christian communities, the future of the Orthodox Church in Belgium and in Luxemburg is in God’s hands. From a human point of view, one could wish that the Orthodox might move towards a deeper rooting in the country where they live while remaining united to traditional and universal Orthodoxy. The Orthodox, despite their diverse origins, are linked by the unity of faith and of sacraments. In the future, they should reinforce their common testimony, without forgetting they are in Western Europe on ancient Christian ground. They have to become conscious, with the other Christians, of the realities of the contemporary world; together they are responsible to be living witnesses of the Gospel.

Selective Bibliography

Good.

ΑπάντησηΔιαγραφή